- Home

- Deborah Markus

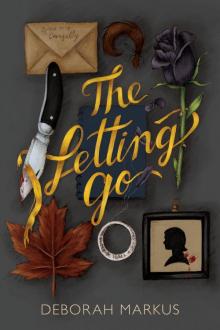

The Letting Go

The Letting Go Read online

Copyright © 2018 by Deborah Markus

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously.

Sky Pony Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Sky Pony® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyponypress.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Kate Gartner

Cover image credit Sarah DiBlasi-Crain

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-3405-0

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-3406-7

Printed in the United States of America

Interior design by Joshua Barnaby

To Dominick Cancilla and Markus Cancilla,

who were with me every word of the way.

“The past is not a package one can lay away.”

—Emily Dickinson

NOTEBOOK 1

(in some particular order)

One need not be A Chamber—

to be Haunted—

One need not—be A House—

The corpse that showed up yesterday was a stranger. I can’t figure out if I’m supposed to be relieved by that or not.

I haven’t seen it. Him. They won’t let us, of course.

Even the picture they showed us was from before it happened. His driver’s license. He had his wallet with him when he was left here, which I suppose was lucky for all of us.

There might be pictures later, online, of how he looks now, but I don’t want to look at them.

If I were supposed to see, wouldn’t he have been left somewhere just for me? Or am I old enough now that I’m expected to take a certain initiative with this sort of thing?

I didn’t know him. None of us knew him.

Ms. Lurie didn’t know him, but she found him anyway.

There’s something awful about that—not just for her, but for him. Dying shouldn’t be like that. Being practically tripped over by a stranger is a terrible way to start your death. It makes everything you did in life hardly count at all. It makes you “the body” forever after.

Of course it couldn’t have been very pleasant for Ms. Lurie, either. She was just taking one of her usual early-morning walks. She always comes back from them looking even dreamier and kinder than usual, talking at breakfast about how beautiful a morning is when no one else has seen it yet.

I wonder if she’ll ever talk like that again.

Maybe she will. Maybe she’ll think about the hundreds of walks she’s taken without seeing any corpses at all. Statistically speaking, this particular morning doesn’t even signify.

I’m not sure that’s how people think about things.

I’ve never been any good at understanding how normal people think.

I do know Ms. Lurie always tries to focus on the positive.

There’s a lot of that to focus on in this case, though she may not realize it. She may have already learned, for instance, that it’s a good thing everyone here knows she’s always up and around at five in the morning. Maybe she was a suspect for a few minutes—finding the body always makes you look bad—but it was probably just a formality.

She’s also lucky that the body she found was shot in the back of the head. That’s fairly tidy, as murders go. Though I suppose that depends on what you have to compare it to.

It was a stranger. Not one of her students or teachers, not a friend, not family. Not someone she loved.

And of course she only found the one body.

I couldn’t tell her how lucky she is even if she’d be willing to listen, though. That isn’t the kind of luck anyone feels thankful for. It’s all about what isn’t true rather than what is.

Plus I’d have to tell her how I know so much about this particular subject.

I wish I knew if this is my fault.

Is it starting again, or could it just be coincidence?

Is murder ever a coincidence?

I didn’t know him. I know I didn’t know him.

As usual, no one’s rushing in to tell me what the rules are. If this is supposed to be a sign that they’ve changed

The problem with writing in ink is that when you don’t know how to end a sentence, the beginning just sits there staring at you.

I love ink and paper—that’s part of my project at Hawthorne—but they’re not always very convenient.

I hope Stephen James (former artist, current corpse) doesn’t mean I have to stop playing with them here.

I like Hawthorne. It’s pretty and quiet and safe.

Or it was quiet, until yesterday.

I wish he hadn’t come.

It’s Easy to invent a Life—

God does it—Every Day—

They let me keep my first name when they changed everything else. I don’t know if they were being nice to me or just practical.

Probably practical. They wouldn’t want to go to all the work of changing things only to have me give it all away and make them do it all over again. And it’s hard to learn to react naturally to a new name. It looks bad if there’s a big pause when someone says your name, or if you look surprised or puzzled by it.

Not that many people speak to me, but there will always be a few. Especially now, while I’m still in school. Even this school.

Emily is a common enough name that they must have decided it wouldn’t be an automatic giveaway.

They let me pick my new last name, because I suggested something completely different from my old one and also completely ordinary.

I didn’t want a middle name, but most people have one so they said I should, too. The whole point of my new name is to disarm suspicion, after all. It was their idea, so I left it to them to choose. It’s not as if I’m ever going to use it.

Maybe it was fun for them to get to play around with names for a change, instead of their usual legal mumbo jumbo.

I’m not even just Emily to anyone here. I don’t have any friends, of course, and the day I met my assigned mentor I told her to call me Miss Stone. She looked as if I’d just given her a fresh frog sandwich, but tried to smile at me anyway. “That’s a little formal, isn’t it?” she asked.

“I can write it down for you, if you need to practice saying it,” I answered.

She leaves me alone now. If I want to talk to her, I know where to find her.

I was named Emily after my mother’s favorite poet.

I guess saying Dickinson was her favorite poet is misleading, since my mother didn’t actually like any other poets. She thought most poetry was boring, trite, or pretentious—sometimes all three, if the poet really worked at it. But my mother was assigned some Dickinson in high school, and she was hooked. Just fell in love. Extra hard, the way you maybe feel when you never expected to even like anyone and then you find yourself wanting to propose five minutes after the first hello.

She told my father he could choose the names for any boy babies they might have, and she let him pick my middle name, but she always insisted that if their first baby was a girl, she had to be an Emily.

That was me. Their

first child, who turned out to be their only child.

Maybe they were planning on more.

Maybe I wasn’t supposed to be this alone.

Maybe I was supposed to have a sister, like Dickinson did.

Maybe my mother would have tried to convince my father to name her Lavinia, after Dickinson’s sister. Maybe she would have pretended to insist on that name, just for the fun of hearing my father say she could name his child Lavinia over my dead body. Maybe she would have replied who said it was YOUR child? And he would have pretended to stomp out in a huff and she would have called him back laughing and said all right, we can name her whatever you want—how about William? I’ve always liked William. Just for the fun of seeing him stomp and huff again.

I was too young to hear about their plans in the child department, and then their plans died with them.

I suppose my Dickinson project is a way to connect with my mother. And partly a way to thank her for giving me the one name I’d be allowed to keep.

If you’re reading this, whoever you may be, I’m safely dead and can stop lying to the world. That’s what this diary is: a place where I can tell the truth and not have to worry about what might happen next.

That doesn’t mean I’m not allowed to lie to myself for the fun of it. My life needs a rewrite more than most.

All that nonsense about who I was named for is a story I felt like telling myself today. I’ve loved Dickinson ever since I stumbled across a poem of hers when I was little. I liked her because we had the same first name, and then because she’d written what was supposed to be a letter from a fly to a bee.

For all I know, my mother hated Dickinson.

But that’s not the story I want to be in.

No one is ever going to tell me about my mother, so I can make up any kind of origin story I want.

My name is Emily, and I’ll never know why. I only know it’s mine.

When everyone else was taken away, I got to keep Emily.

Of Tolling Bell I ask

the cause?

“A Soul has gone to

Heaven”

I’m answered in a

lonesome tone—

Is Heaven then a Prison?

We all woke up to the sound of the alarm.

I’ve heard it before, but only during drills. For a few seconds I thought this must be just another test, but then I woke completely and saw what time it was. Early morning; barely light.

Either this was the real thing or we were supposed to think it was.

There’s a Sherlock Holmes story where he makes a woman think her house is on fire just so he can see what she tries to take with her when she has to flee the building. In my case, I had a collection of Dickinson’s poems next to my bed, and while I’m not sure I would have fought my way through flames for it, it was comforting to take it with me.

I didn’t smell smoke, or see any whispering its way into my room. I touched the door before I opened it and it didn’t seem hotter than usual.

I noticed all this in a leisurely, distant sort of way. Either I was genuinely calm or I was numb with terror.

I remember being glad, as I opened the door and saw other students filling the hallway, that the clothes I sleep in are actual clothes—sweatpants and a long-sleeved T-shirt, in this case. And I’d automatically stepped into my fleecy moccasin slippers.

The girl in the room next to mine, on the other hand, was wearing only a long white nightgown, complete with eyelet lace and bits of pink ribbon at the cuffs and neck. She was barefoot. I hate being barefoot, even when it’s hot out. She didn’t seem to mind, though, or even to notice that in the dim hall she looked like the ghost of a wedding dress.

“Is it a fire, do you think?” she asked me, sounding conversational.

I shook my head.

Hawthorne Academy is proud to have room for only a couple of dozen students—“independent scholars”—but just then it seemed as if there were hundreds of us, all pouring out into the same narrow hallway and wondering what to make of it all.

“I don’t smell smoke,” another girl said authoritatively.

“Then let’s go to the lounge,” the girl in the white nightgown said. She was answering the other girl but looking at me. “We’re supposed to gather there if there’s an emergency.”

I looked away. Gather there? What century was she from?

She was right, though. And just then, Vera, one of Hawthorne’s teachers—“mentors”—joined our group.

“Let’s go, girls,” she said. “Everything’s fine. We just have to get to the lounge, okay?”

“If everything’s fine,” one of the girls protested in a panicky voice, “why do we—”

“Follow Lucy, please,” Vera said, nodding toward the girl who had mentioned the lack of smoke. Lucy nodded importantly in reply and turned to lead us away. Vera added, “I’ll be right there. I just want to check the rooms and make sure everyone’s up and out.”

We all started moving in the indicated direction—not exactly running, but almost. Only the girl in the gown seemed unruffled, gliding along with the rest of us as if she were caught in a current.

“It’s probably just a mistake,” she said to me in a confidential tone. “Probably the alarm went off by accident and they’ll be bending over backwards to apologize for waking us so early and depriving us of our salubrious sleep.” She smiled mischievously. “I see quality baked goods in my future.”

I didn’t answer. We reached the lounge, and even before anyone told us anything, two things were clear: there wasn’t a fire, and this wasn’t a drill.

A Prison gets to be a

friend—

There are no grades at Hawthorne Academy for Independent Young Women. No classes, no teachers, and certainly no homework. Or maybe it would be more accurate to say there’s nothing but homework. Which isn’t so bad when you’re the one assigning it to yourself.

We do what we want here, at our own pace and setting our own goals. We work in our rooms or the lounge or the library or under a tree. (Ms. Lurie draws the line at letting us actually climb the trees, to the deep disappointment of one budding artist.) We have access to a decent number of books and all manner of art supplies—and Ms. Lurie is always happy to order more—but mostly we have peace and quiet and solitude. Kind of like a convent, but without any pesky praying and people calling you “Sister Emily.”

Most Hawthorne students end up going Ivy League—it’s all in the brochure—but that doesn’t happen automatically and it’s not supposed to be the point. The point is to give a certain kind of artistic type the space she needs to develop her talents and realize her visions and find fulfillment in this quiet, beautiful, rural setting.

Also in the brochure, and also surprisingly true.

Coming to Hawthorne after all those dismal boarding schools was like walking into a rose garden from an unlit cellar.

We mostly get painters and writers, but every now and then there’s a composer or a potter to mix things up a bit. Once we had a violinist, but she started pining away and they had to send her home.

Ms. Lurie started this school almost twenty years ago. At first it was just her big rambling house in a little artist’s colony of a mountain town in coastal California. Ms. Lurie raised her four daughters here following the same recipe she uses on us now: never telling the girls what to do, just listening to their ideas and giving them guidance and letting them decide how they wanted to live their lives.

It turned out that they wanted to live their lives as two famous actors, a famous singer, and a famous artist. So Ms. Lurie decided to make a career of nurturing sensitive souls in a secluded setting, and up until this week it’s worked out fine for everyone involved.

It’s making me a little crazy trying to figure out if her luck ended on my account or if dead bodies sometimes just turn up where no one expects them.

1 Pound Sugar—

½—Butter—

½—Flour—

6—Eggs—<

br />

1 Grated Cocoa Nut—

Mrs Carmichael’s—

Dickinson used to write poems on almost anything—a chocolate wrapper, edges of envelopes, even the back of a recipe she’d jotted down. Or maybe the poem was supposed to be the front. Nobody knows which was more important to her: a poem about the things that can never come back or a friend’s recipe for coconut cake.

She loved baking, so maybe she loved the recipe and the poem equally.

There was a stack of flyers in the lounge that morning, and some pens. So I was able to write down some of what happened while it was happening.

It would have been tidier to copy those scribbles into this notebook, but I thought it was more in the spirit of Dickinson to tape them in here.

I guess it was also very Dickinson of me to scribble my thoughts on whatever scraps of paper were at hand. At the time, though, I felt like an idiot for having left this notebook back in my room.

At least it was in a drawer. The police wouldn’t have been looking for a murderer or maybe another dead body in my night table. They wouldn’t know to care about anything I’ve written down.

No one knows I’m at Hawthorne except Aunt Paulette and a few other people who don’t care where I am as long as it’s nowhere near them.

They Shut Me Up in Prose

As when a little Girl

They put me in the Closet—

Because they liked me “still”—

Nobody’s told us anything yet. They look like they wish they didn’t have to tell us whatever it is that’s going on. They just want us to sit still and know nothing.

Ms. Lurie came to talk to us for a few minutes. She was trying to be both comforting and vague, which is a frightening combination. It means the truth is too scary to tell.

She said Something’s very wrong and she said Don’t worry, you’re all safe, everyone’s all right, and you could tell she wanted to be able to say them at the same time.

“Why did the alarm go off?” a girl asked, sounding as if she were trying not to burst into tears.

The Letting Go

The Letting Go